Júlia Major

Dear Grandma,

Since we live in the world we do, I would like to ask your permission to write about you, so that I don’t violate your personal rights and so that what I write is authentic! I want to show you as you were: cheerful, kind, joyful, honest, and full of love. Among my ancestors, you were the one who was born the longest ago, during the time of the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy, and I was fortunate enough to know you. You lived through World War I, when you were still a little girl, aged 7 to 13. I don’t know how much you understood of what was happening around you. What was it like when the world suddenly changed and they couldn’t operate on your eye, which became infected at birth and developed a cataract? All this had an impact on your entire life, and not just yours, because if your sight had been perfect, I wouldn’t be writing these lines now, as I wouldn’t even exist. I try to imagine what your childhood must have been like as the first child of Róza Major. You were the eldest in the tailor family. My great-great-grandfather, Gyula Major, was a famous tailor in Újlak (Ujlak), and you all learned tailoring and sewing from him. Aunt Rózsi, your youngest sister, was a famous seamstress; fashionable women came to her from Szőlős (Vynohradiv) to have clothes made. I’ve jumped ahead in time again, but perhaps only because you didn’t tell me much about your childhood. All your siblings had cheerful names, just like you: Lulu, Marcsa, Kucu, Rózsi were the girls, and Gyula was the only boy, who unfortunately died young. You lived across from the Greek Catholic church in Újlak. Grandma Róza bought the house when she came home from America, where she had worked for two years. For years, it was the gathering place for the family and all the relatives, where we came together for holidays.

I’m trying to piece together the history of Subcarpathia (Kárpátalja) based on your life. I found your birth certificate; it wasn’t hard, as you faithfully preserved the family treasures—the photos and family tree data—which Nagymamicska (my paternal grandmother) could recite by heart all the way back to the 1700s.

So, World War I ended, and I see that your birth certificate is already written in Czech. You were 12 or 13 when the Czechs took power and drew the borders. What must it have been like when suddenly you couldn’t go to Tiszabecs or Debrecen? You couldn’t visit relatives and friends you had often met before.

In the video we made of you, you talk about going to Kassa (Košice) to have your eye operated on. You were a pretty young girl of 24 then, and they gave you a serenade beneath your hospital window. You also recounted in detail the dress and the shoes you arrived in at the hospital. How happy you were! How much you enjoyed the serenade! As it turned out, you never met that young man again. Unfortunately, one of your eyes could no longer be saved, and you were given a glass eye, which you lived with for the rest of your life.

They said you wanted to become a nun. You took it so seriously that you applied to the convent, but they rejected you because (in their opinion) only girls who were completely healthy could belong to Christ. A girl with a glass eye could not be part of the order. Perhaps it was only because God had a different plan for you…

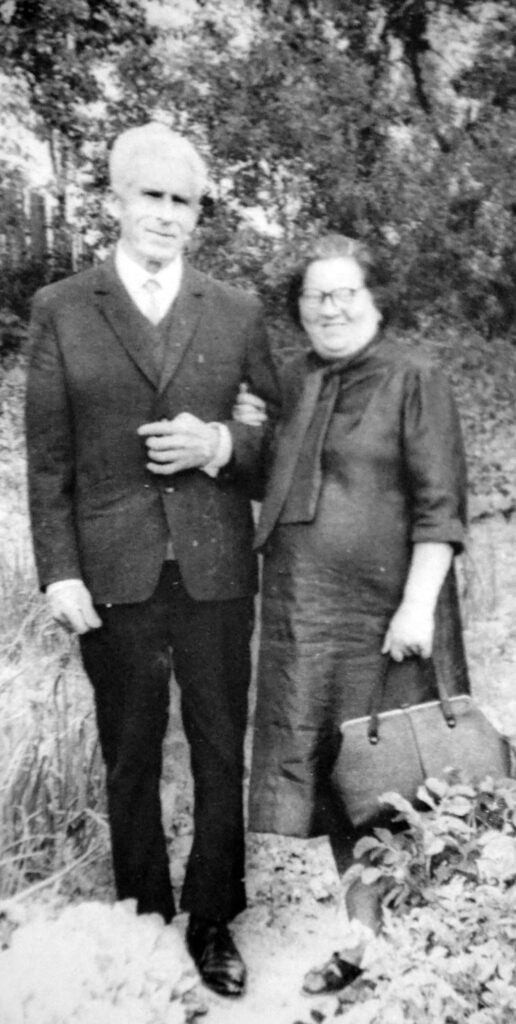

Grandpa also lived in Újlak. His parents moved there from Debrecen—I’ll never know why, even though all four of his grandparents were native to Debrecen. Jóska Boros, a dashing young man, appealed to you, too. “I’d save up for that young man,” you said to the person who jokingly suggested he would be your husband. Since words have power, it happened, though it wasn’t easy. The son of a Reformed presbyter could not marry a Catholic girl; the world had never heard of such a thing. So Grandpa decided to leave the Reformed Church and convert to Roman Catholicism.

I don’t know the year you got married, but after the great happiness came World War II. You didn’t talk about the war and the difficulties that followed, and no one talked about the Gulag either. How did you live during that time, what gave you strength when the foreign armies arrived? You didn’t say. I only heard one story. Grandpa was away at the war. They didn’t know if he was still alive. One dawn, a beggar knocked on the window. He was thin, dirty, and tormented. The children were still sleeping. Grandma asked him what he wanted, and then she recognized her husband in the beggar. He looked so bad that she had to throw away his clothes. She bathed him, cut his hair, shaved his beard, and put clean clothes on him, only allowing the children to see him then because she was afraid the little ones would be frightened of him.

Nagymamicska, or Angel as great-grandpa called her, was only small then, 4 years old, and you were 28. I was surprised when I calculated it; she was born quite late for that period. You gave life to four children—József, Angéla, Gyula, and Ferenc—whom you raised with love. They grew up during the glorious era of the Soviet Union. How much changed during that time! Electricity was introduced, and a TV even arrived in the house, which you carefully covered with a cloth before going to bed. You moved from Újlak to Szőlős, and on your neat, clean house, there was a sign written in Hungarian on a colorful plaque: “Tidy yard, orderly house.” I wonder who started that sign program and what its purpose was?

I remember you lived nearby, on Piszareva Street. I was very small, 4 years old, when my sister, who was 1 at the time, and I walked to your house. I hadn’t put shoes on Andi, and we arrived barefoot and muddy. You clapped your hands and quickly washed and changed us. We got hot cocoa, broke bread into it, and drank it from a tin mug. Grandpa bought us bean sugar, which is what only we called it. It was white chocolate-glazed peanuts; we loved it! We never heard a harsh word from you. Perhaps only when you poured hot water into Grandpa’s aluminum washbasin, and he didn’t notice and put his hand in.

I was five when you sold the house in Szőlős and moved back to Újlak, leaving a terrible emptiness behind in me. I couldn’t go to you anymore to drink barley coffee or cocoa. Grandpa used to cycle. He even rode from Újlak to Khust, waking up at dawn and setting off, arriving by noon. On those days, he would come to our place in Szőlős to rest for a while. He wasn’t young anymore, having been born in 1901.

Dear Grandma, you even saw my wedding dress. Even with one eye, you noticed it was wrinkled. Sadly, you didn’t live to see my wedding, but you were certainly there in spirit, just as you live in my memories today, smiling and cheerful. If you were alive, you would be 118 years old this year.

With love,

Ildikó February 9, 2025.